FROM SOLUSI TO STRINGS. Part 1.

Maleka Charles

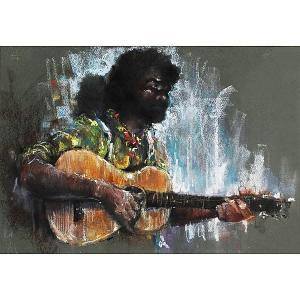

Seated alone under the shade of an apricot tree, Tapiwa strummed his guitar, trying to coax a song to life. He experimented with various chords and rhythms, hoping to finally strike the perfect note.

“I have a song in my mind.” He said. “But it doesn’t want to come out.” He fashioned a transient smile of contentment around his lips.

A close friend, Mandla — who seemed to admire Tapiwa’s strumming even more than I ever did — told me that Tapiwa had been wrestling with the guitar strings since that morning.

“He woke me up around six to tell me he has a song and needed my help to hit the right note.” He said, rolling a joint of weed in between his fingers.

“My man you don’t understand.” Tapiwa said. “Sometimes for the right note to come we must connect with the ancestors, so that they give us songs.”

He was speaking of his late grandfather, uMachonisa, who passed away in 1998. Stories from the village say that uMachonisa was a renowned guitar player in Zimbabwe during the 1950s.

He had toured the world, captivating audiences with the magic at his fingertips. In 1952, Machonisa was celebrated as Africa’s best rumba artist. Before his passing, the Zimbabwean-born musician had already amassed a remarkable collection of awards across Africa and Europe.

“Old man was the best my man.” Tapiwa said. “I hate death, I really hate it.” His face emphasized a very deep shadow of anger against the hand of death, which had mercilessly taken grandfather from him so soon.”

As a rill of tears welled in his eyes, I could feel the tension of frustration radiating through every fiber of his being.

The memory of his late grandfather washed over him with an inevitable pang of poignancy. “You really loved your grandfather, neh?” I asked.

“Dearly.” He said smilingly, his world was now becoming deurmekar and the acid jazz of sorrow pitilessly gnawed at his bosom like mice would a cheese.

“Eish! I need to smoke now.” He said, looking cravingly at Mandla, as he gingerly curled a cloud of smoke in the nearest of air. “Bafo maziche phela!” Tapiwa finally said.

“For how long have you been playing guitar?” I asked. “It’s been a while now.” He said, pulling an empty grade of beer that idled three feet from where he sat, he placed it before himself and implored that I sit down.

“Thank you.” I said. Bewitched by my humbleness and inquisition, Tapiwa flashed at me a wide smile of amiability I personally could not resist.

“I was twelve when grandfather taught me the strings.” He hoisted the joint of weed to his dry lips and took rather a long pull of smoke and ferociously puffed away into air in the end.

“Twelve!” I cut in. “Sure!” his eyes took up a more vivid form of life now and his countenance flowered into a sheer resilience as if the dawn in Christmas morn.

“From Solusi to strings baba.” He burst into a shout. “Zikuchayile manje.” Mandla said, breaking into a giggle. “Ah! Wena” Exclaimed the stoned Tapiwa.

He closed his eyes and began to hum softly. Nodding like the elephant grass swaying in the wind, he tenderly tapped his fingers on the guitar before suddenly bursting into song.

“Ndiya hamba

Ndiya hamba

I’m going home

Yeah! Yeah.”

“Ndiyo bona

Ndiyo bona

Isthandwa sam’

Nomvula wam’.”

“I’m going home

I’m going home

I’m going home

Yeah! Yeah.”

No sooner had he finished singing and returned to humming, than a friend, completely captivated by the melody, recited a short poem to breathe new life into the song.

“Where is Umangobe?

The coal train from Nyamandlovu

The locomotive of the dry and barren lands

Umangobe the homeless child

Tell him the sons and daughters are crying

For the milk of their mothers’ breasts.”

“Where is Umangobe

The coal train from Nyamandlovu

Mbizeni! To come and fetch us from the concrete jungles of Johannesburg.

Safangendlala eGoli, engabe ipeke kuphi iZimbabwe uma sila madoda?”